Support LFS Hardship Grants by ordering an LFS Awareness Day Elephant Shirt! But... why elephants?

The TP53 gene is a tumor-suppressor gene, often called "the guardian of the genome." In this post, Living LFS member Ilonka Dee shares how research into elephants, with their plentiful copies of TP53, offer promise to those with Li-Fraumeni Syndrome.

"Each of the cells in our body contains two functional TP53 alleles. Even with these two functioning TP53 alleles, 50% of all men and 33% of all women will develop cancer in their lifetime. However, the absence of one functional TP53 allele leads to the cancer predisposition syndrome known as Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (LFS).

LFS presents with nearly 100% lifetime cancer risk, multiple primary tumors, and early childhood cancers. Even in the absence of LFS, 50% of all tumors harbor a mutation in the TP53 gene, indicating that p53 plays a critical role in protecting our bodies from cancer." - Schiffman Lab, Huntsman Cancer Institute

Why does an elephant get less cancer than a human?

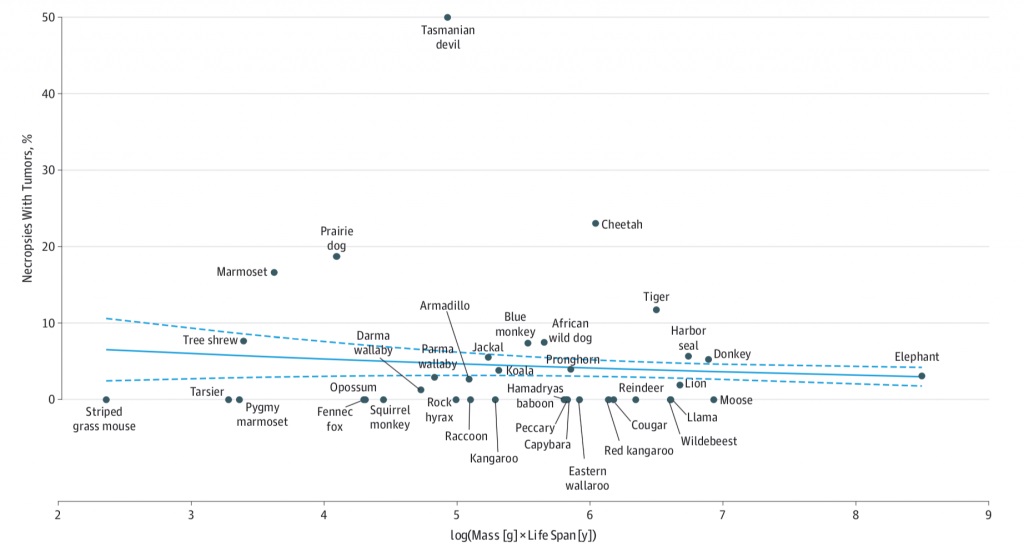

Peto's Paradox (formulated in 1977) states that the development of cancer is not related to the size of the organism and the lifespan of that organism. In 10 years time, young elephants grow from an organism of 100 kg to an organism with more than 3000 kg of cells. Theoretically speaking, if every cell has the same chance of degenerating into malignancy, an elephant should develop many times more cancer than a human. The opposite turns out to be true. How is this possible?

Elephants have a 5% lifetime chance of dying of cancer compared to 11-25% in humans. It turns out that elephants have many more copies of the TP53 gene. Summarized in layperson's language we can determine that a healthy person has 2 soldiers working in their body to help clean up derailed cells, which could become cancerous. People with LFS only have 1 soldier, while an African elephant has at least has 40 cancer fighting soldiers!

In 2014 I found out I have LFS during treatment for a triple negative breast cancer relapse. My soldier was probably exhausted from working overtime, and clearly couldn't handle all the derailed cells that were thrown towards her on a daily basis. Finding out I have LFS was a weird kinda relief. In a way it felt like a confirmation that it wasn't something caused by myself, that I wasn't doing something terribly wrong in my daily life which was causing these terrifying cancers. At that point in life I'd battled leiomyosarcoma in 2002, triple negative breast cancer in 2012, and my oldest son Kaj had neuroblastoma stage 4 in 2012. I am what they call "de novo," aka the starter, the first in my family line to have this mutation named Li-Fraumeni.

Dr. Joshua Schiffman's elephant research

In May 2017 I got the opportunity to be able to attend the LFS International Conference in Toronto. Dr. Joshua Schiffman was one of the very inspiring speakers during this multi-day conference. Schiffman, who had cancer as a child and still sees patients, sees himself as a triple threat to cancer: cancer survivor, cancer researcher and cancer doctor.

Dr. Schiffman at the Huntsman Cancer Institute and his research with elephants focuses on why elephants get cancer much less often than humans.

What I personally find very reassuring to know is that the research on elephants requires occasional blood samples, but Schiffman can use blood drawn during routine exams and so imposes no pain or testing on the animals.

“My view is that nature is always going to be smarter than people... We can work as hard as we want in the laboratory. But the elephants have already figured it out,” Schiffman says.

His research focuses on trying to figure out how to either modify human genes to create more copies of this cancer-fighting DNA or to trigger the same body function another way. He works to understand how elephant p53 function is enhanced compared to human p53, and hopes to apply these mechanisms of cancer resistance to develop and test effective treatments for cancer.

Previously on elephant research:

LFS in the News: PBS NewsHour Report on Elephants, Cancer, and TP53 (2016)